Part 8 – Glowing Gospels

Above: “XPI AUTEM” © STOCKHOLM, NATIONAL LIBRARY OF SWEDEN, MS A. 135, FOL. 10R

A Discovery

“…as my eyes grew accustomed to the light, details of the room within emerged slowly from the mist, strange animals, statues, and gold – everywhere the glint of gold. For the moment – an eternity it must have seemed to the others standing by – I was struck dumb with amazement, and when Lord Carnarvon, unable to stand the suspense any longer, inquired anxiously, ‘Can you see anything?’ it was all I could do to get out the words, ‘Yes, wonderful things.” ― Howard Carter, Tomb of Tutankhamen

Lord Carnarvon, Lady Evelyn Herbert and Howard Carter at the steps leading to Tutankhamun’s tomb in November 1922.

When I was in the 6th grade, our teacher showed our class a film on the discovery of King Tutankamen’s tomb in Egypt. Films were a big deal back in my day. Our classroom did not have a television or VCR, so if we were to watch something, it was on a reel-to-reel projector. And the movie, which came in a large round container, had to be ordered well in advance from the state library. We would wait in anticipation as the teacher carefully threaded the film into the projector, the lights were turned out and shades pulled over the windows. It was all very exciting, and I’m sure this is lost on my children who were practically born with screened devices in their hands.

I can still see the film’s title image, the death mask of King Tut – its smooth golden perfection, up on the screen. That day opened a whole new world to me. The level of craftsmanship exhibited by the Egyptians was superb, and I was immediately captivated. In middle school and high school I explored and read ALL things Egyptian – every report, every project assignment was an opportunity to learn more. In 8th grade I read the complete writings of Howard Carter (weird, I know), and I have the volume sitting on one of my many book shelves even now.

Out of this youthful craze, came a longing to become an archaeologist or at least study archeology. I loved art, but I also loved the prospect of digging, discovering, and the mystery of it all. Once I got to college, I found myself leaning wholly into art, while archeology’s appeal somewhat faded. But there is still an archaeologist that lives in me – that part of me enamored with exploration and discovery. Even writing this blog series is a somewhat of an archaeological venture. I can spend/waste hours online digging for great stories and fun tidbits. “Father Amazon” delivers new books to my home almost every week (I may have a slight problem).

Journey to the Celts

In 2016 I signed up for a tour/pilgrimage through Scotland, England and Ireland learning about the Celtic Christian faith and exploring its ancient roots and early beginnings – this trip was so amazing. In preparation, participants were encouraged to read a number of books along with an additional packet of information about Celtic theology, the sights we would be visiting and the Christian saints associated with them. Given my pension for ancient mysteries plus art and theology, I had no problem whizzing through the suggested reading as the trip drew near.

I learned Celtic Christianity really begins with a man named Patrick (as in Saint Patrick, celebrated on March 17) in the 5th century. God placed a call on his life that he was unable to ignore. After receiving theological training at a monastery in what is now modern-day France, Patrick returned to Ireland where he had been a shepherd slave as a teenager. Patrick shared the gospel among the pagan people of Ireland.

What developed out of Patrick’s 40 years of ministry was a whole new branch of Christianity, one that grew and spread largely apart from the influence and oversight of the Roman Church. The Church back then was actually quite afraid of the Celts with all their warring and witchcraft, but thankfully not Patrick who was able to see the good in these people. Patrick had a unique sensibility in both evangelizing and allowing these new Christians to discern for themselves how they would organize their church structures and practices. (A very “reformational” approach, don’t you think?) Patrick also taught the Celts to read and write which meant they could now study Scripture and listen to what God spoke to them through it. (Any pope who might have heard such a thing would surely have fallen over and died right then.) The Celts did not develop the hierarchy of power and position that Rome so clearly modeled, and often they allowed women to hold positions of leadership (can you hear the Roman cardinals and bishops screaming?). It isn’t until a few hundred years later that Rome began to notice what was going on up on those northern islands. The crack-down on the Celtic Christians was anything but kind, gracious or amicable.

The World’s Finest Gospel Illustrators

It’s quite amazing how Patrick’s influence seemingly transformed a culture of warriors into monks and nuns who now craved knowledge and literacy. The Celts/Irish were soon on their way to becoming book lovers and book makers extraordinaire. Thomas Cahill writes in his book, How the Irish Saved Civilization, about just how critical to saving the world’s body of literature these new Christ followers were. Their newfound desire to learn had them traipsing around Europe, gathering up important literary books. Back home they would busy themselves with the work of making copies:

“Nothing brought out Irish playfulness more than the coping of the books themselves, a task no reader of the ancient world could entirely neglect. At the outset there were in Ireland no scriptoria to speak of, just individual hermits and monks, each in his little beehive cell or sitting outside in fine weather, copying a needed text from a borrowed book, old book on one knee, fresh sheepskin pages on the other.

Even at their grandest these were simple, out-of-doors people. (As late as the ninth century an Irish annotator describes himself as writing under a greenwood tree while listening to a clear-voiced cuckoo hopping from bush to bush.) But they found the shapes of letters magical. Why, then asked themselves, did a B look the way it did? Could it look some other way? Was there an essential B-ness? The result of such why-is-the-sky-blue questions was a new kind of book, the Irish codex; and one after another, Ireland began to produce the most spectacular, magical books the world has ever seen.” – Thomas Cahill, p. 164-65

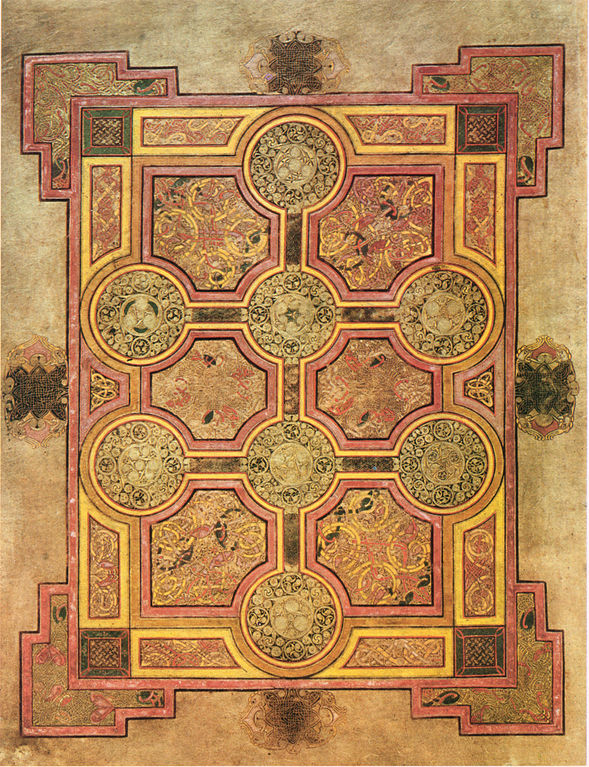

The Eight-Circle Cross (folio 33r) from the Book of Kells – the carpet page preceding the Gospel of Matthew

The Chi-Rho Page (folio 34r) from the Book of Kells

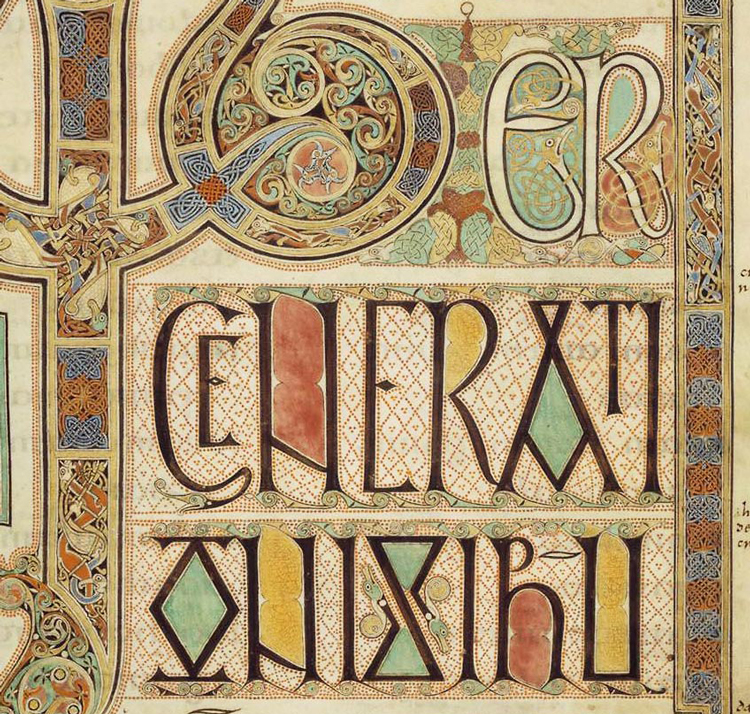

The Book of Kells, now displayed at Trinity College in Dublin, Ireland, is held as the greatest of these books. It is a hand-illustrated or illuminated, hand-written Latin volume of the four Gospels. No other manuscript approaches the magnificence of ornamentation and artistry in this volume. The Chi Rho page, as it has been named, featuring the Greek initials (XPI) for Jesus Christ sits among the greatest works of Christian art in the world to date. The decoration is so tiny, so intricate, many a scholar has contemplated the possible use of some type of magnification device to create it.

Learn more about the Book of Kells >

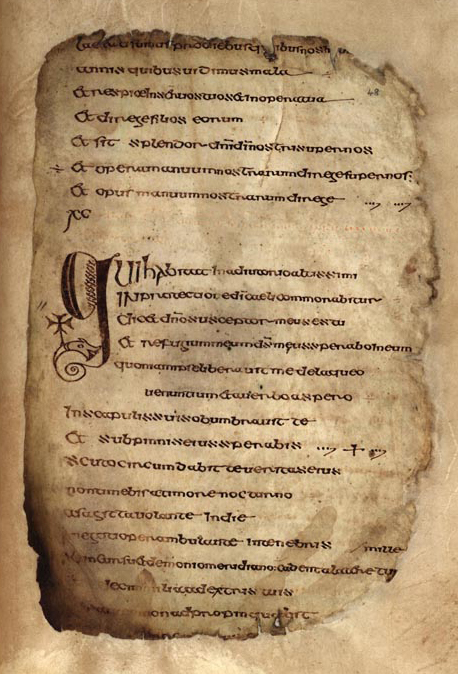

The Psalter of Columcille or the Cathach of St. Columba (folio 48r), 6th century Irish

The form of Irish illustrated Bible texts (of which many fine volumes still exist), their decorative pages and features, are attributed to a monk named, Collumcille (or Columba) who, having been banished from Ireland, traveled to Scotland and established a monastery on the Isle of Iona. Collumcille spread the gospel to the Scottish and English on the mainland just as Patrick had done in Ireland. Now Collumcille was also a great lover of books…

“…especially beautifully designed manuscripts. As a student, [Collumcille] had fallen in love with his master’s psalter, a uniquely decorated book of great price. He resolved to make his own copy by stealth, and so we find him sitting in Finian’s church at Moville, hunched over the coveted psalter, copying it in the dar. According to legend, he had no candle, but the five fingers of his left hand shone like so many lights while his right hand assiduously copied.” – Cahill, p. 170

Collumcille’s copied Psalter, known as the Cathach of St. Columba, still exists and is housed at the Royal Irish Academy. It is believed to be the second oldest Latin Psalter in the world.

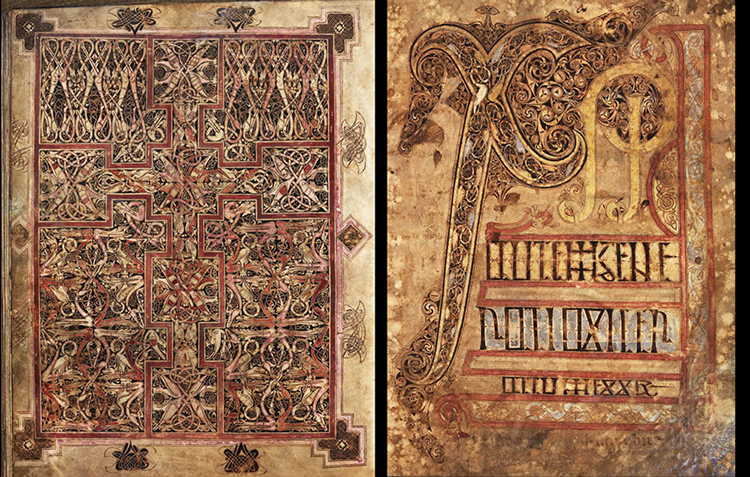

Carpet page and Chi-Rho page from St. Chad Gospels (AD 700-800). Photo by British Museum.

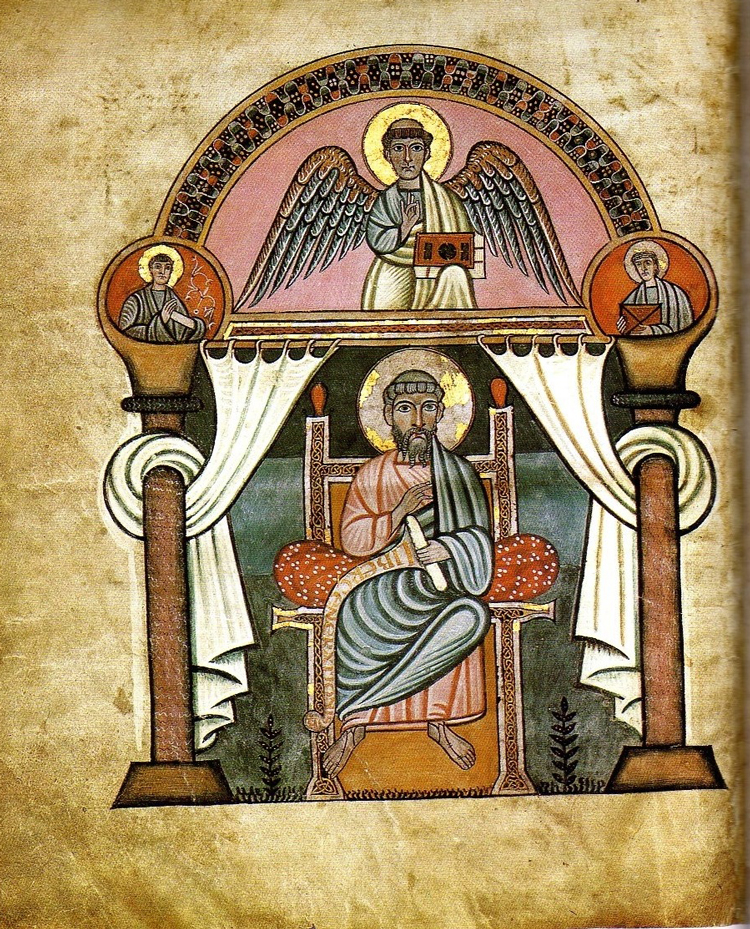

Portrait of Matthew with angel symbol (folio 9) from the Stockholm Codex Aureus – mid-8th century from Canterbury

Key features of Celtic illuminated gospels include:

- Portraits of the gospel writers and their respective symbols as designated by Jerome:

- Matthew – angel

- Mark – lion

- Luke – calf

- John – eagle

- Carpet pages – decorative pages of largely geometric ornamentation preceding the beginning of each of the four gospels

- Beginning text pages marked by an exquisite monogram followed by colorful and decorative text in large capital letters that diminish in size gradually down this opening page

- Illustrations of key events in the life of Jesus

- Symbols or decorative drop caps noting important passages

- Lettering outlined in red dots to give a glowing effect to the “the living Word”

- Intricate knot work and spirals distinctive of Insular art – that of the Celtic people

The work of creating an illuminated gospel or psalter was a devotional activity or an act of private worship for the artist. The work was incredibly labor intensive and artists would spend hour upon hour at their craft. Many of these gospel volumes were collaborative projects with more than one individual contributing. One may have written the text, another created the illustrations and a third the intricate carpet pages and beginning text pages. The finished book was often used in public worship or for evangelism. In the Celtic Christian tradition, it was the written word that was given decorative attention while worship spaces remained fairly simple and without much adornment.

My Howard Carter Moment

At the very end of my 2016 Celtic pilgrimage, I had the opportunity to visit the Book of Kells at Trinity College in Dublin, Ireland…

The exhibit is packed with visitors. At the end of the large entry room filled with various displays on the history, craftsmanship and notable features of the gospel volumes was a staircase leading visitors to a much smaller upper level room where the volumes of the book were on display. The room is dimly lit with a large glass case at its center. A few at a time, visitors could approach the book for a look. A 30-second glance is all most individuals seemed to give this legendary work of Christian art.

I finally make it to the case. My eyes have now adjusted to the low light (so as to preserve this precious artifact), I lean over the glass. The book is not as large as I was expecting. The pages virtually move with their intricately woven Celtic knot work, small precise shapes, mysterious creatures and figures. It’s as if it is alive, it’s breath-taking! I don’t want to leave, honestly. I want to keep studying these few pages. To be polite, I step to a corner of the room and then hop back in line for a 2nd view…3rd view…4th view…By now the rest of my tour group has long left the display and many have headed to a Sunday worship service at one of the cathedrals in Dublin. I decide to make this display my morning worship experience. In my opinion, few works of art in the world have given God such glory and honor.

Final Thoughts

Beginning of Gospel of Matthew (detail of folio 27r) from the Lindisfarne Gospels, 7th-8th century

The Celtic Christians could be thought of as Protestants ahead of their time. Much of their theology and practices align well with the thoughts and beliefs of the the early reformers. In fact, many Protestants are now rediscovering and exploring this branch of the Christian church. Here you will find a deep love and respect for nature and an understanding that life with God permeates each moment of daily live – all that we do or think or say. To these doctrines the Celts have given magnificent visual testimony. For in their decorative interlacing of shapes and spirals, creatures and colors lie the interweavings of a complex, yet ordered universe, the mingling of heaven and earth, and the divine dance of God with man.

I found it somewhat sad how after standing in line for an hour or more outside, people so quickly whizzed through the Book of Kells exhibit there at Trinity College. In their haste to push through the crowds and be able to say that had “seen” the great book, what had they missed? Had this book affected them in any way? Had they truly gazed into and grappled with the mystery that can be found here? Did they depart having received a gift from this encounter?

In 1185, Giraldus Cambrensis wrote this description of a book (possibly even the Book of Kells) he had an opportunity to view in Kildare, Ireland:

“…if you take the trouble to look very closely, and penetrate with your eyes to the secrets of the artistry, you will notice such intricacies, so delicate and subtle, so close together, and well-knitted, so involved and bound together, and so fresh still in their colorings that you will not hesitate to declare that all these things must have been the result of the work, not of men, but of angels.” – Giraldus Cambrensis

Every week when I post to Instagram and Facebook about this blog series, I get a pretty low response. I totally get it and I’m completely aware that what I post goes against the social media grain…I’m not promoting a hiliarous cat video to go watch, or featuring some adorable pictures of my kids or the family fun we just had over the weekend. Encouraging others to read about/meditate on artwork (let alone church history) just isn’t a regular/popular thing, not to mention the time it takes, something we seem to have so very little of these days.

If you are still reading this post, I thank you. But seriously, I want to encourage you to choose one of the images above and spend some time with it this week…even just 5 minutes while you sip your first cup of coffee in the morning. It’s a great practice, it’s a way to focus your mind on something positive and uplifting:

- Observe the colors and the shapes

- Find the part of the image you like the best

- What does the image make you think about?

- If you could talk with the artist, what would you ask them?

“Can you see anything?”… “Yes, wonderful things!” ― Howard Carter, Tomb of Tutankhamen

Down an Ancient Path

The BIRCH TREE STUDIO BLOG